The East

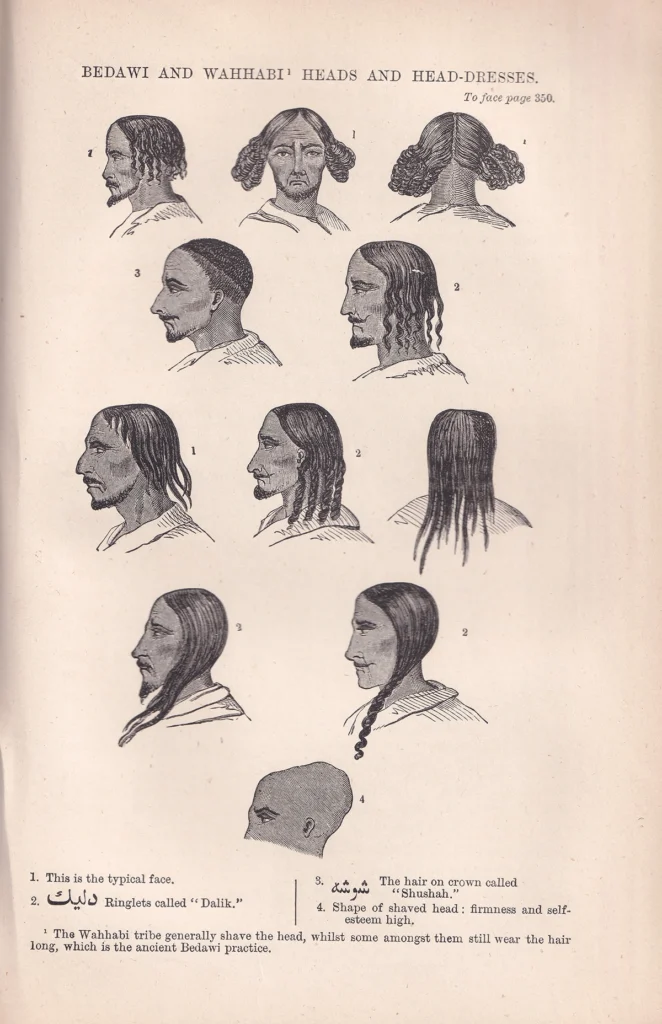

The prototype for the 19th century traveler – adventurous, tireless, curious – is undoubtedly the Briton Sir Richard Francis Burton, who arrived in Trieste after a life of wandering around the world, remaining there until his death. All of Europe talked about his trip to Medina and Mecca in 1853, disguised as an Arab, as well as his expeditions in search of the sources of the Nile. But his books dedicated to India and Pakistan, which he encountered in his youth, after enlisting in the East India Company, to North and South America, to Iceland, and to Equatorial Africa, were also famous.

Baron Pasquale Revoltella, a shareholder in the Suez Canal who left his magnificent townhouse and huge assets to the city of Trieste, dedicated a precious and detailed travel diary (1861-1862) to Egypt. The spirituality of ancient Egypt, combined with the suggestions of other beliefs and spiritual tendencies, is found in the poem Aurora Borealis by Theodor Daübler, a bohemian and wanderer, who developed his original poetics during years of wanderings in Greece and the Near East.

From North to South

The experience of Carl Weyprecht, an adoptive triestino, was as a protagonist and chronicler of the Austro-Hungarian expedition to the North Pole in 1872-1874, composed mainly of sailors from the Adriatic who spoke to each other in Italian as well as in dialect. Weyprecht is also remembered for having established the International Polar Year 1882-1883 in which the first collaborative scientific research projects began which would go on to become another of Trieste’s excellences.

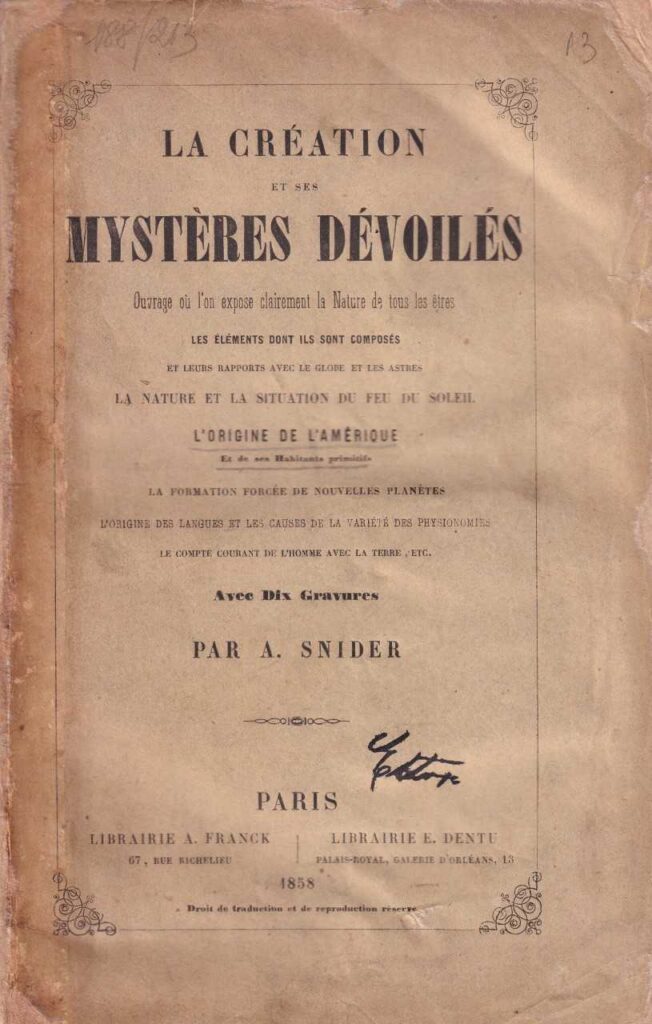

Domenico Lovisato, an Istrian bound to Trieste so tightly that he wished to be buried with its halberd flag, headed in the opposite direction. Having failed in the objective of an expedition to Antarctica, in 1881 he carried out a long exploration of Patagonia, described in a series of diaries now preserved in the Trieste Civic Museums of History and Art. In one of his pages, which remained long unpublished, Lovisato put forward a theory of continental drift which had already been hypothesized by another traveler and man of letters from Trieste, Antonio Snider Pellegrini, back in 1859!

From Outside to Inside

Trieste entered the descriptions of the great 18th century adventurers, such as Giacomo Casanova, who stayed in the city between 1772 and 1773 and Mozart’s librettist Lorenzo da Ponte. We find it in the descriptions of romantic travelers engaged in the Grand Tour and in the papers of many diplomatic writers. In 1874 the French writer and designer Charles Yriarte stayed in Trieste and later published a lively guide entitled Trieste e l’Istria in which he declared that he wanted to publicize a city still unknown to many, but rapidly expanding at that time.

Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere (2001) is the story of a city different from any other, perhaps indefinable, in which the author, Jan Morris reflects on herself, examining the mutability of her own life. She arrived in Trieste as a British army officer in 1945 and returned several times after gender reassignment surgery, as the woman she felt she was. Her description has become in some way paradigmatic of the attempts to describe an elusive Trieste, to which the more recent La città celeste by Diego Marani (2021), a coming-of-age novel and declaration of love for the city, also belongs.

From Inside to Outside

Travel books sui generis are the guides to Trieste written by people from Trieste, including Tre giorni a Trieste, edited by, among others, Baron Revoltella way back in 1858, to Trieste by Silvio Benco in 1910, up to the “Guidina” di Trieste by Corrado Premuda (2020), designed especially for younger readers. More authorial and personal guides include Trieste sottosopra by Mauro Covacich (2006), which shows the hedonistic side of the people of Trieste, while Trieste selvatica by Luigi Nacci (2019) illustrates the link between Trieste and the wild Karst which embraces the city through the voices of poets and writers.

Other works by Nacci, a writer of the viandanza, the practice of traveling on foot through an area to better understand its populations, history and characteristics, introduce us to a series of books from Trieste which, faithful to this inspiration, tell of slow journeys: on foot, by bicycle, at most by train or boat. They include the long explorations, halfway between diary and reportage, of Paolo Rumiz, a well-known journalist and correspondent of the Balkan wars, or the playful cycling adventures as retold by Diego Manna.

On board!

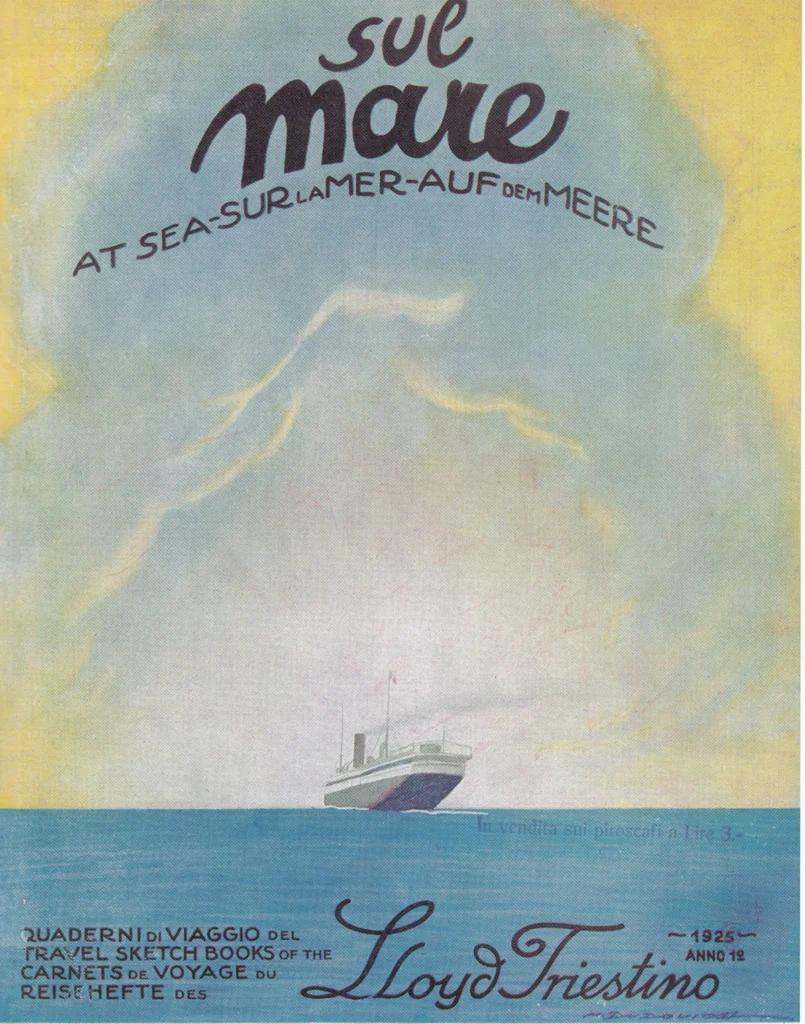

With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Trieste became a gateway to the East which opened to the Red Sea, Africa, India, China and Japan. Lloyd Austriaco (later Lloyd Triestino), Tripcovich, Austro-Americana and Cosulich were the leading companies in this adventure which, in the 20th century, also included routes to the Americas, Australia and Israel, not always for pleasure.

In fact, wealthy tourists discovering exotic destinations and emigrants driven by economic necessity or persecution sailed the same seas. In the 1920s and ’30s Trieste was one of the “Gates of Zion” through which Jews passed on their way to building the new state of Israel, an experience that we find described in Giorgio Voghera’s books Quaderno d’Israele (1967) and Carcere in Jaffa (1969).