The fairy tale that theaches

Starting from the pioneering and courageous translation of The Arabian Nights edited in 1880 by Sir Francis Richard Burton, which appeared scandalously licentious to his contemporaries, Trieste experienced a vast production and collection of fairy tale repertoires. In this case, however, the national question was not extraneous to the genre and children’s books were often entrusted with the role of patriotic education, according to a classic German romantic interpretation.

Fairy tales that were part of popular tradition were adapted to local contexts so that Cenerentola (“Cinderella”) in Trieste, in Istria became La Cuzazenere and, in Slovenian, was renamed Pepelka. Rich in allusions to Trieste and Slovenian culture, the story Martin Krpan by Fran Levstik remains in print, always with new and original illustrations, since its first edition in 1858.

Books, Radio and Comics

Between 1909 and 1911, even Scipio Slataper published some romantic fairy tales including Il petalo di rose and La veglia del mare. Alberto Boccardi’s children’s production was courtly and moralizing while Ugo Mioni’s more fantastic and daring tales tried to rival Salgari.

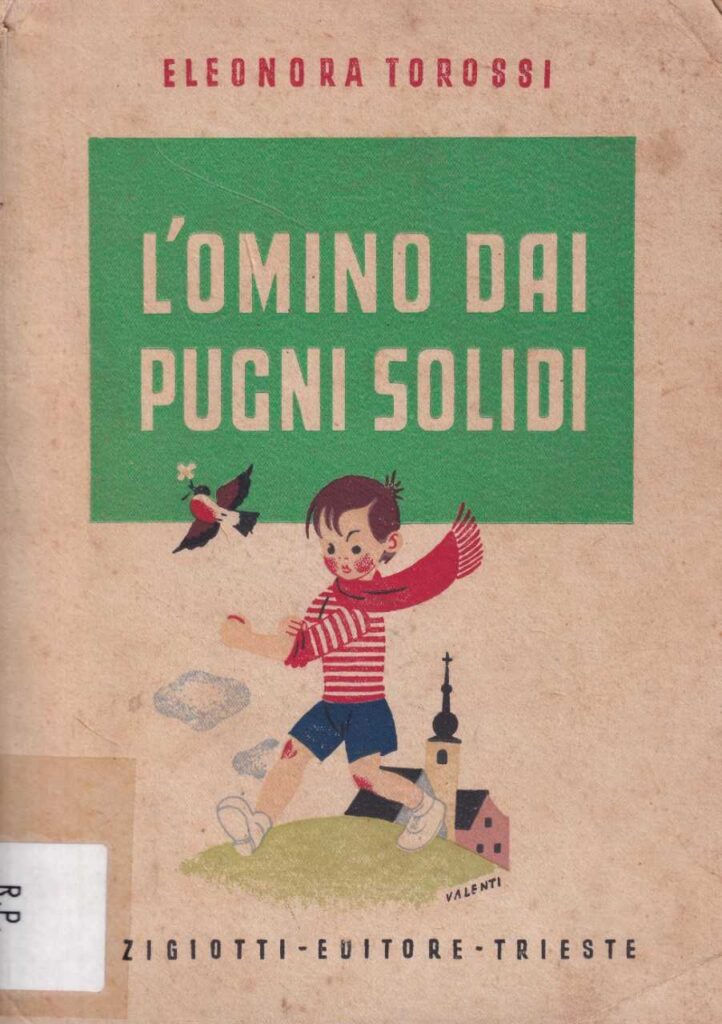

Several writers – Haydee, Lucia Tranquilli, Pia Rimini and Eleonora Torossi – collaborated on the “Giornalino della Domenica” and in 1920, “Il Piccolo dei Piccoli” was published which had among its editors Oreste Giovannini, the pseudonym of Baccio Ziliotto.

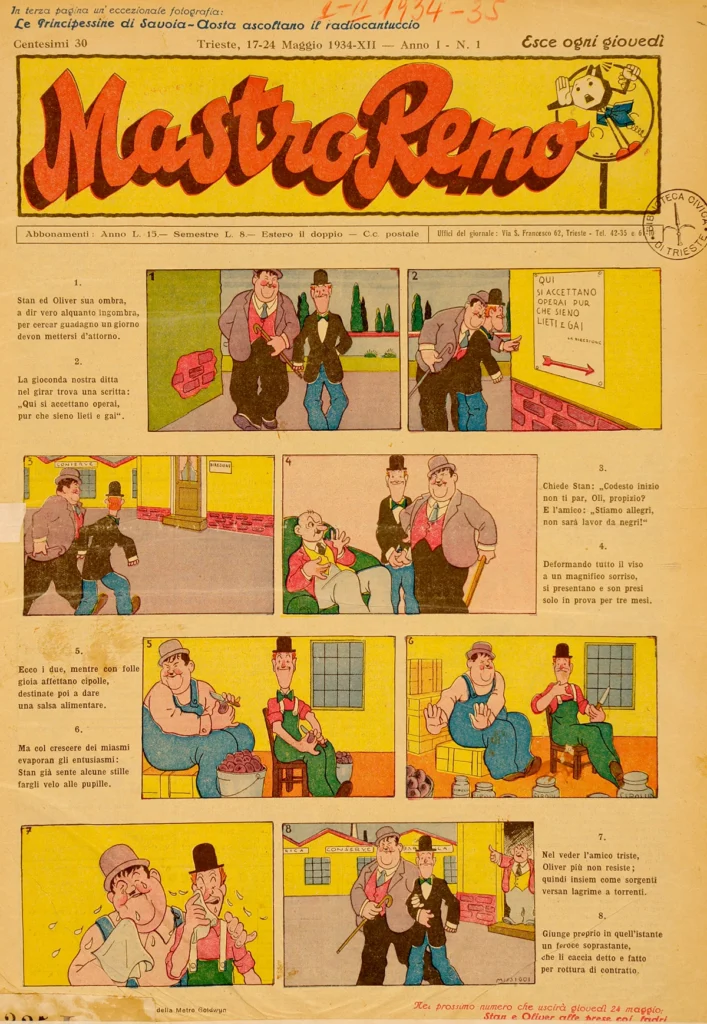

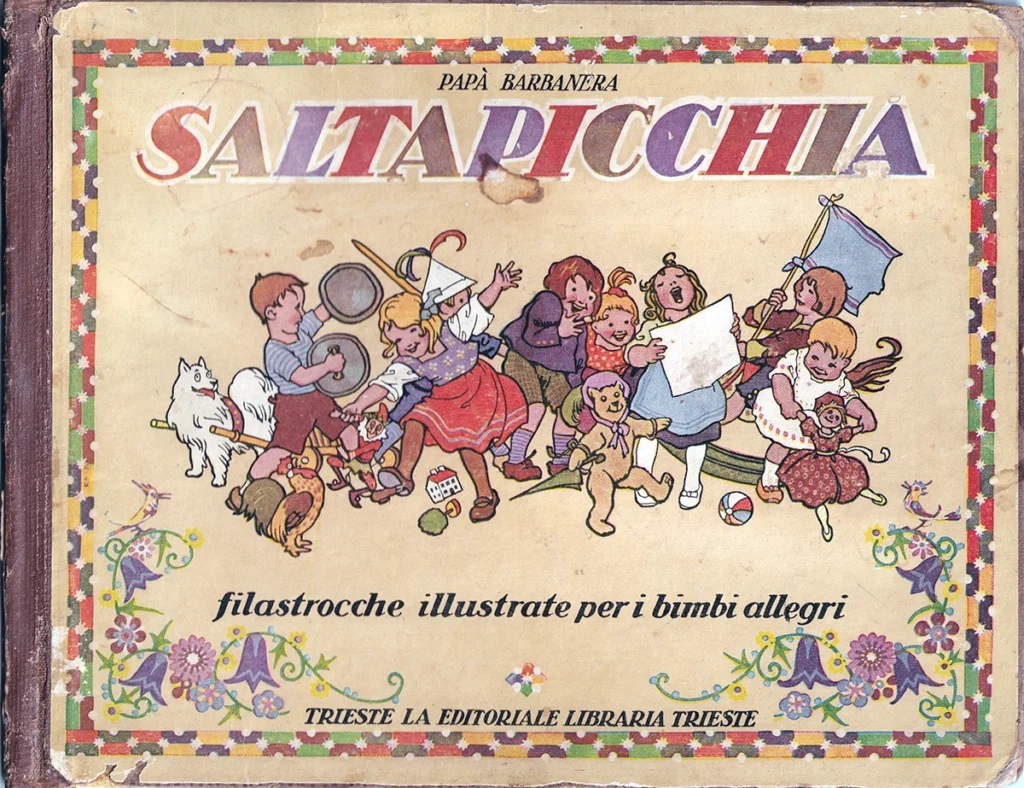

The last director of the “Piccolo dei Piccoli” was Mario Granbassi who later embarked on the radio adventure Mastro Remo. This broadcast gave rise to the illustrated children’s newspaper of the same name (1934) printed by Editoriale Libraria. The periodical was the first example in the history of Trieste journalism of an illustrated newspaper for children. Later, the works of Lina Galli, Bice Polli and Ketty Daneo were to appear, while, at the end of the 1950s, Donatella Ziliotto established herself as a writer, translator and critic who directed editorial series and curated programmes for Italy’s State broadcaster, the RAI.

Trieste illustrates

Between the two wars a golden period for Trieste publishing opened, due in no small part to the activity of Editoriale Libraria (today Edizioni EL) with its refined, illustrated publications including the successful Storia di Pik Badaluk (1922). Discovered by Anita Pittoni, much later EL also promoted the talent of Nicoletta Costa, who published her drawings in the editorial series L’Armonica. Zibaldone degli scritti brevi for La storia del pesciolino piccolo (1966) by Marino Todeschini.

Olindo Missigoi and his cartoons on Laurel and Hardy, Le storie di Mammalucco by Lauro Lah Laghi, the drawings of Alice Zeriali (appearing in the “Mastro Remo” comic), the comics by Mario Alberti and Lorenzo Pastrovicchio, the graphic novels of Walter Chendi and Paola Ramella, the graphic transposition of Pahor’s Nekropolis created by Jurij Devetak and that of Il richiamo di Alma by Mattioni, drawn by Vanna Vinci, as well as the literary illustrations by Max Calo and Raimondo Pasin: all go to show that the intertwining between the written word and the drawn line is very close.

Other stories, other authors

Fulvio Tomizza (with Trick. Storia di un cane, 1975; La pulce in gabbia, 1979) and Stelio Mattioni (Anno 2077: un racconto di fantascienza, 1977) also try their hand at stories for children and Gianni Rodari in Il libro degli errori (1964) dedicates La bora e il ragioniere, published separately in 2020, to Trieste and its wind. The dedication and productivity of the authors of children’s literature such as Luciano Comida and Ugo Vicic seem to deny the proverbial laziness of the people of Trieste to whom Italo Calvino dedicated his story La scienza della fiacca (Figo caschime in boca) included in the collection Fiabe italiane (1956).

![Hochzeit im Walde. Bilder von Else Wenz-Viëtor; verse Adolf Host, Leipzig, Alfred Hahn's, [1921] > coll. BC Hortis](https://lets.trieste.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/hohzeit-in-walde-892x1024.webp)