![F. Faltus, Cattedrale di San Giusto, 1850 ca. / Nicolo Pertsch, Trieste, Nuovo tempio di Sant’Antonio Taumaturgo, 1830 ca. / G. Broili, N. Pertsch, Chiesa greca orientale [di San Nicolò], 1830 ca. / G. Bernardi, A. Rieger, G. Giuliuzzi, Facciata della chiesa dei Padri Mechitaristi in Trieste, 1859 ca. > coll. BC Hortis](https://lets.trieste.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/scritture-cover.jpg)

Judaism

Many of the protagonists of the city’s cultural life came from the Jewish community, prosperous and numerous in Trieste before the Holocaust. They included Italo Svevo and Umberto Saba, Giorgio Voghera, Giorgio Pressburger and Ferruccio Folkel among the writers, the psychoanalyst Edoardo Weiss, philosophers such as Giorgio Fano, the editors Emilio Treves and Bobi Bazlen, the historian Fabio Cusin, and the scientists Giuseppe Levi and Pierpaolo Luzzatto Fegiz.

Some characteristics of their work are sometimes traced back to the Jewish roots of certain writers, including a tendency towards self-analysis, often resulting in selfcriticism, the consequent interest in psychoanalysis, together with a particularly elevated sensitivity, and even a certain inclination towards pessimism. The cases of Svevo and Saba, although both distant in nature and destiny

from the religions practiced in the family, have often been investigated in this respect.

Islam

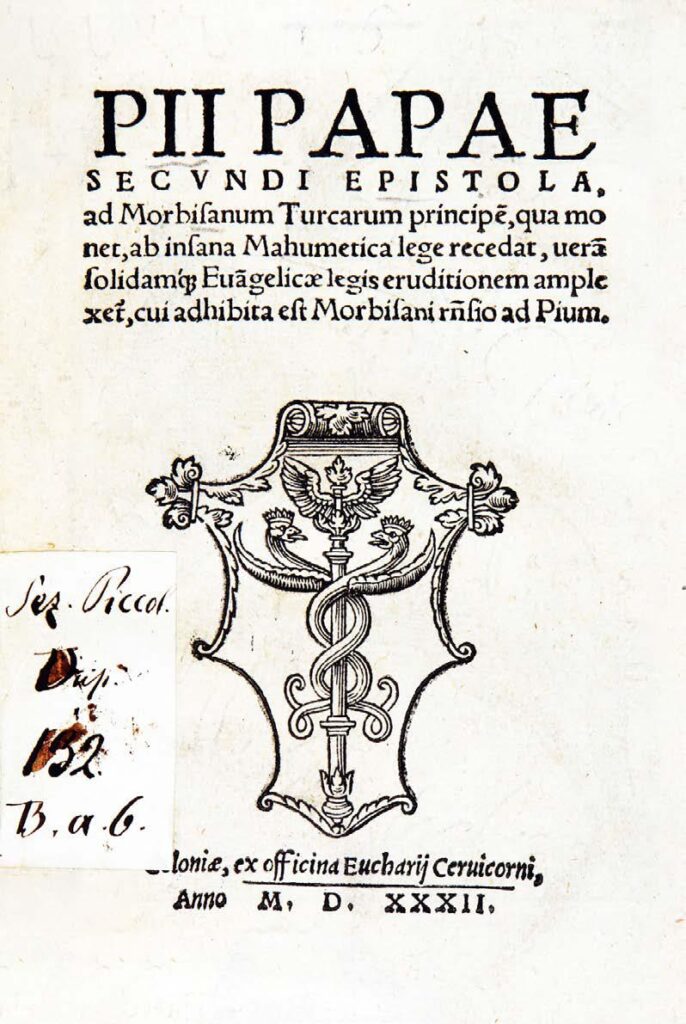

Trieste’s position and contacts with the East are perhaps at the origin of the interest of the writers in the Islamic world. For the time and for the political purpose, we do not go back as far as the Letter to Muhammad II that Enea Silvio Piccolomini, Pope Pius II (formerly Bishop of Trieste), wrote to the sultan in 1461 inviting him to conversion, but we can certainly evoke the many pages that Richard F. Burton dedicates to Sufism, a moderate and philosophical current of Islam, in the verses of Kasidah.

The novel Alamut by Vladimir Bartol was centered on the doctrine of the Ismailis, the sub-sect of Shia Islam within which a cult of assassins flourished, who again in the collection of short stories Al-araf – taking its name from the seventh sura of the Koran – showed his interest in Islamic doctrine. The meeting and clash between Islam and Christianity was central to The Bridge on the Drina and many other works by Ivo Andrić.

Christianity

Spirituality often permeates the pages of avowedly Catholic authors or those who have chosen a Christian religious theme. In Ulysses, the Irishman James Joyce, openly rebellious towards established religion, lays out a comparison between the tolerance of the Jew, Bloom, and the intolerance of his fellow Catholic citizens. Freedom of thought does not undermine the backdrop of faith in many of the Slovenian authors including Kosovel, Pahor and Rebula.

Like Bartol’s Alamut, Rebula’s V Sibilinem vetru (“In the Sibyl’s Wind”) examines the issues of religious tolerance in distant times (the second century AD of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius) to talk about the present with particular reference to the condition of Slovenia under Yugoslavia, as does Fulvio Tomizza in his Il male viene dal Nord, centered on the life of the bishop of Koper, later a Protestant reformer, Pier Paolo Vergerio the Younger.

Another religiosity

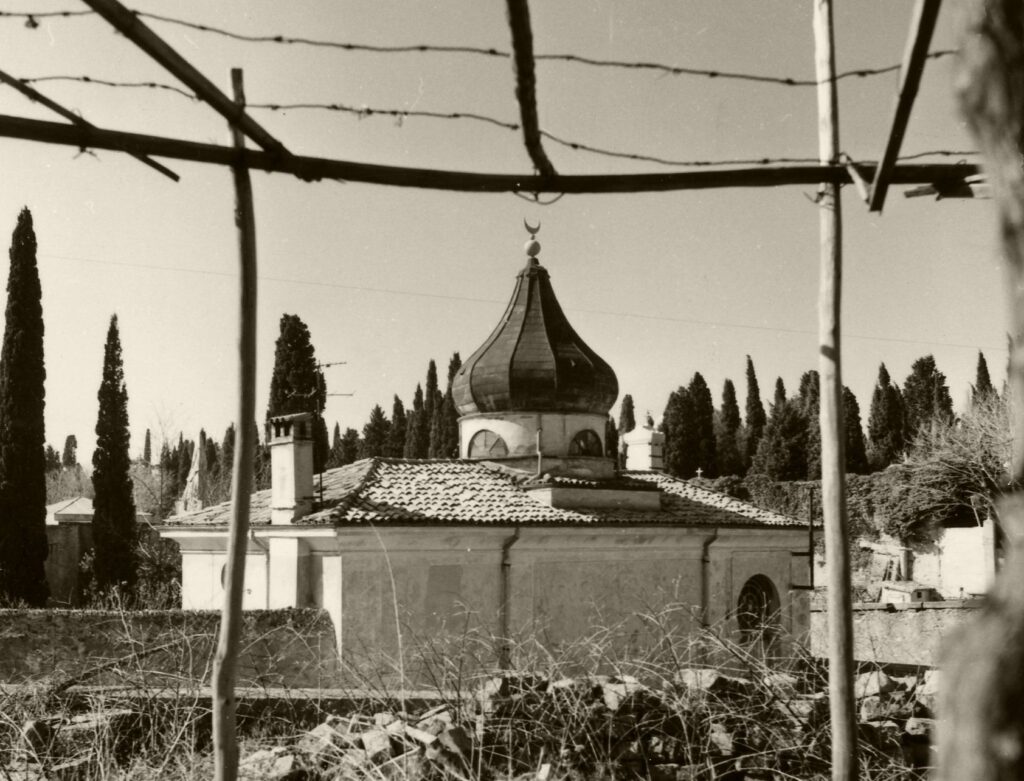

Beyond traditional beliefs and spiritual currents, many writers experienced a painful and ambivalent relationship with the divine. Joyce broke with the faith of his childhood but retained a strong fascination for the liturgies and in Trieste, during Easter, he was a congregant in the Greek Orthodox church. Svevo calmly professed to be an atheist but studied Judaism, read the Lives of Jesus by Renan and Strauss was curious about the Christian radicalism of Tolstoy.

Saba’s relationship with religion was painful and ambiguous as he felt “the two races in ancient combat” – that of his mother’s Judaism and his father’s Catholicism (and that of his beloved Slovenian nurse) fighting within himself, to the point of considering conversion and to reciting the Our Father on the tomb of his dearly loved Lina. A “natural” and syncretistic religious feeling emerges, however, with different nuances in the poetics of Slataper and Daubler. And Susanna Tamaro describes her faith like this: “I am Catholic but super secular and I hate good intentions.”