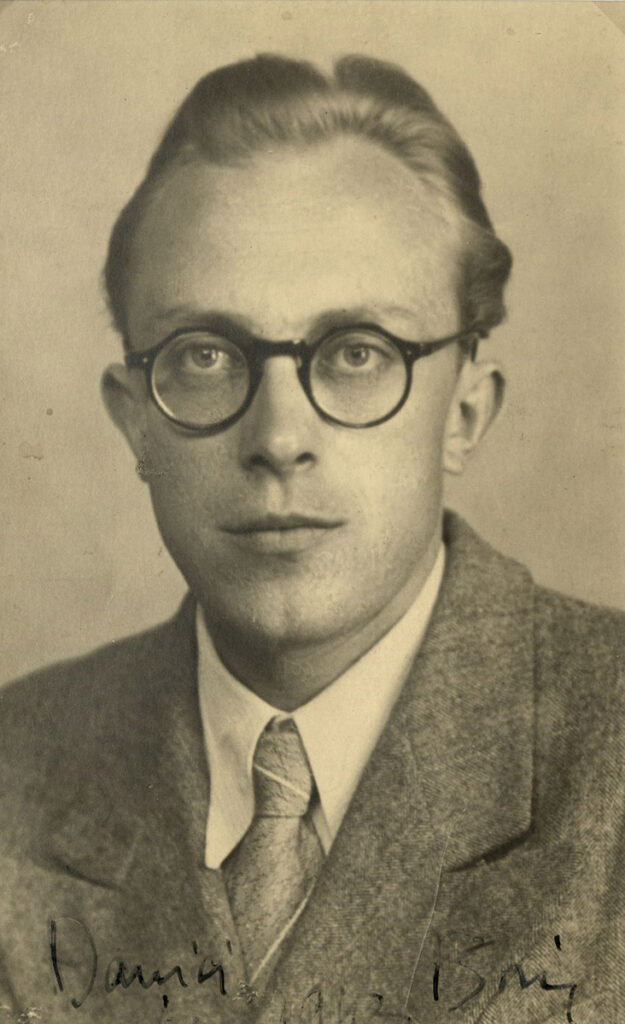

Boris Pahor

From the Bonfire in the Harbour to the Necropolis of the Nazi concentration camps, to his clash with Tito’s Yugoslavia: the long written life of an indomitable Slovenian from Trieste

The first trauma of a life marked by national and cultural conflict for Pahor was the arson attack on the Narodni Dom / Hotel Balkan, the house of Slovenian culture in Trieste, by fascists, in 1920, when Pahor was 7 years old. The experience is retold in the novel entitled in Italian Il rogo nel porto (1959). The violence and denial of Slovenian identity implemented by the fascist regime is at the centre of many of his books including Parnik trobi nji (“The Steamer Sounds Its Horn”), 1964.

Fighting as an Italian soldier in Libya, after 8th September 1943 he went underground and was arrested in Trieste by the domobranci, the Slovenian Nazi collaborators. Tortured by the Gestapo, he was deported to the Dachau and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. He was freed, at the end of his strength, in April 1945. The chronicle of that terrible experience can be read in his most famous work, Necropolis (1967), and in I triangoli rossi (2015), a novel dedicated to political deportees.

The post-war period brought new hardships to Pahor. In the magazine “Zaliv”, which he edited together with Alojz Rebula, he talked about the massacres carried out in Tito’s Yugoslavia of Slovenian collaborators, the same domobranci who had also arrested and tortured him. The article aroused strong echoes throughout Europe and ostracism from the Yugoslav authorities. Pahor won international recognition only very late in life, following the success achieved in France.

Vito Timmel, Incendio del Balkan, 1941 – coll. CMR

From Monrupino to Alamut

The landscape of the Karst, classical literature, religions, history: everything is both lyrical and political for the Slovenian writers of Trieste.

Srečko Kosovel

Born and raised in the Karst, but educated in Ljubljana, Kosovel is one of the most representative voices of Slovenian avant-garde poetry. Although he died at just 22, he left behind more than a thousand poems, hundreds of pieces of lyrical prose, essays, diaries and letters. His lyricism is impressionist when he describes the Karst landscape, expressionist when he imagines the destruction of Europe, constructivist when he mixes collages, mathematical formulas, various colours and styles, but is always powerful.

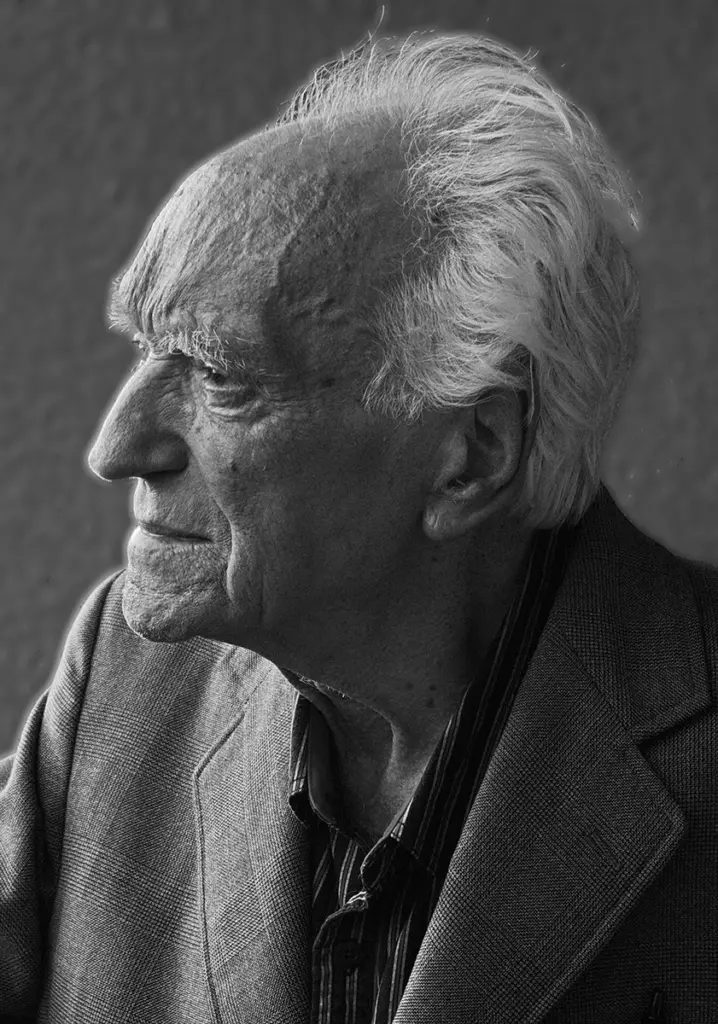

Alojz Rebula

A son of the Karst Trieste, he combined his love for the landscape and the wind of his homeland with that for classical literature, which he studied in Ljubljana and taught in Trieste. In his work, he combined a deep-rooted Catholic faith, a fervent national sentiment and a courageous dissidence. In 1975 this led him, together with Boris Pahor, to challenge the Yugoslav communist regime in the name of an unshakable humanistic ideal.Vladimir Bartol

From Trieste to Ljubljana, Paris, Belgrade and back again. Bartol was a cosmopolitan intellectual who was interested in Islam in the novels of Al-Araf (1935) and above all in his masterpiece Alamut (1938) in which he revived the legend of the Old Man of the Mountain and the deadly Ishmaelite sect of the hashishin, the suicidal warriors. After the attack on the twin towers in New York in 2001, the novel was rediscovered and inspired the famous video game Assassin’s Creed.