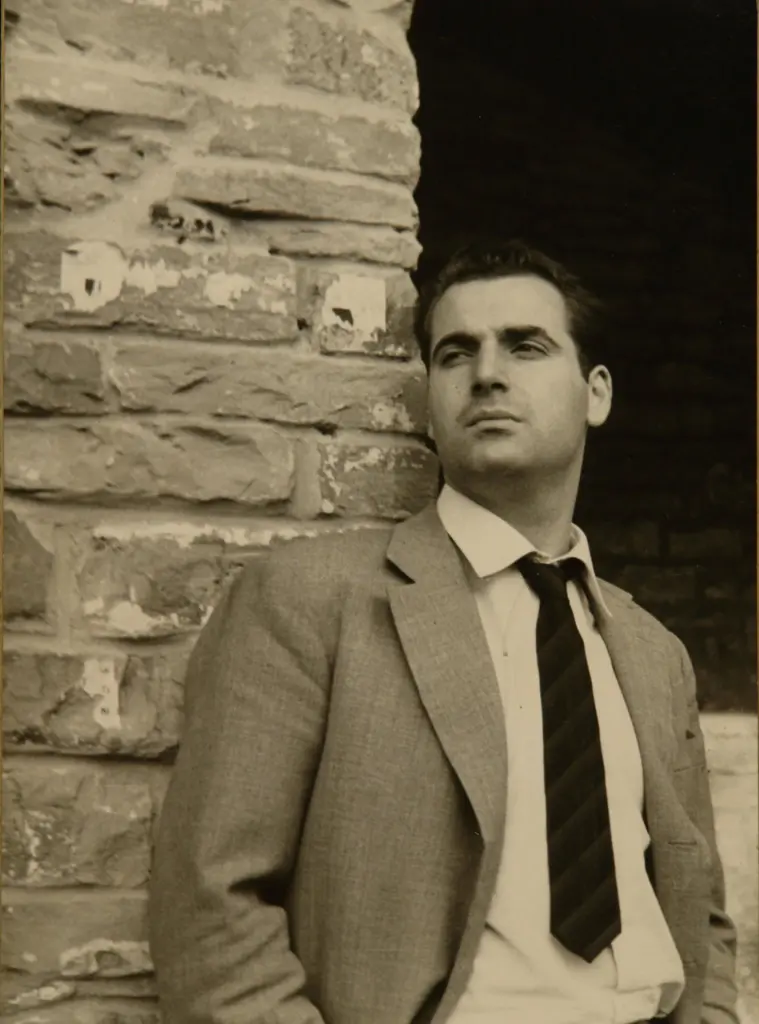

Virgilio Giotti

[Schönbeck Belli]

The friend of Saba who with their Colori recreated impressionist painting in poetry

Born Schönbeck, in art known as Giotti, with a talent for drawing, he attended art school with his painter friends Guido Marussig and Vittorio Bolaffio. To avoid national service in the Hapsburg army he moved to Florence in 1907. Here his talent became poetry in the Piccolo canniere triestino (1914) in which Giotti escaped the lesson of D’Annunzio, getting closer to Pascoli and chooses his own dialect, congenial to his visual poetry and descriptive of the figures and environments of Trieste.

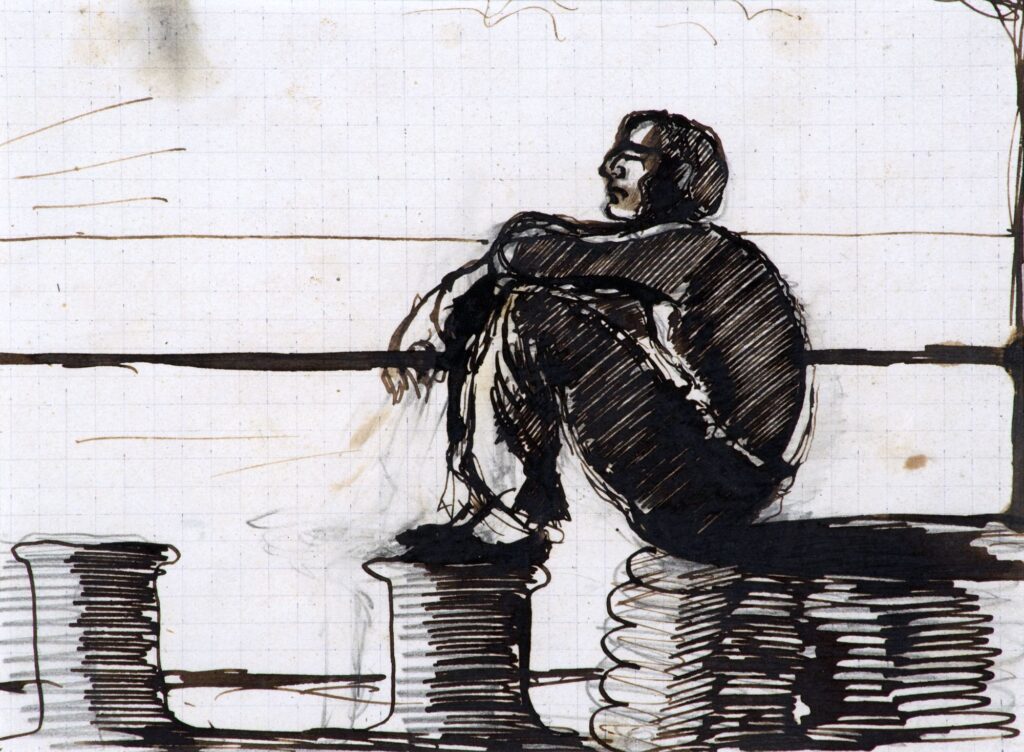

“Excuse me, are you a melancholic?” Thus a young Saba struck up a conversation with a young Giotti one evening. An immediate friendship was established, which would last a long time and lead to an artistic partnership:. Giotti designed the logo of the bookshop for Saba, edited and illustrated Cose leggere e vaganti and the graphics of the ten booklets printed in a few copies, a preview of the Canzoniere of 1921. Saba published – bearing the bookshop’s logo – Giotti’s collection Il mio cuore e la mia casa (1920).

«Scusi, lei è un melanconico?» Così un giovane Saba attacca bottone una sera a un giovane Giotti. È subito amicizia, che durerà a lungo e sfocerà in sodalizio artistico: per Saba, Giotti disegna il logo della Libreria, cura e illustra Cose leggere e vaganti e la grafica dei dieci libretti in poche copie, anticipazione del Canzoniere del 1921. Saba pubblica con il marchio della sua Libreria la raccolta giottiana Il mio cuore e la mia casa (1920).

IN RIVA

De drio del rimitur de àuti e trànvai,

de drio dei alboreti dispossenti,

e dopo de la riva coi camini

dei vaporeti e i casoti e la gente,

xe el mar, xe el ziel. E mi vardo quel mar

e quel ziel nudi, grandi, e me consolo.

In quel mar, in quel ziel xe quel che vòio,

xe quel che bramo e speto.

* /re-mi-tur/ sm – disorder, confusion, bauble, pandemonium, disarray

The derivation from the French demitour (half-turn) brings us back to the evolution made on parade by the soldiers of Napoleon’s garrison in Trieste, to the sound of drums, and the clattering of them.

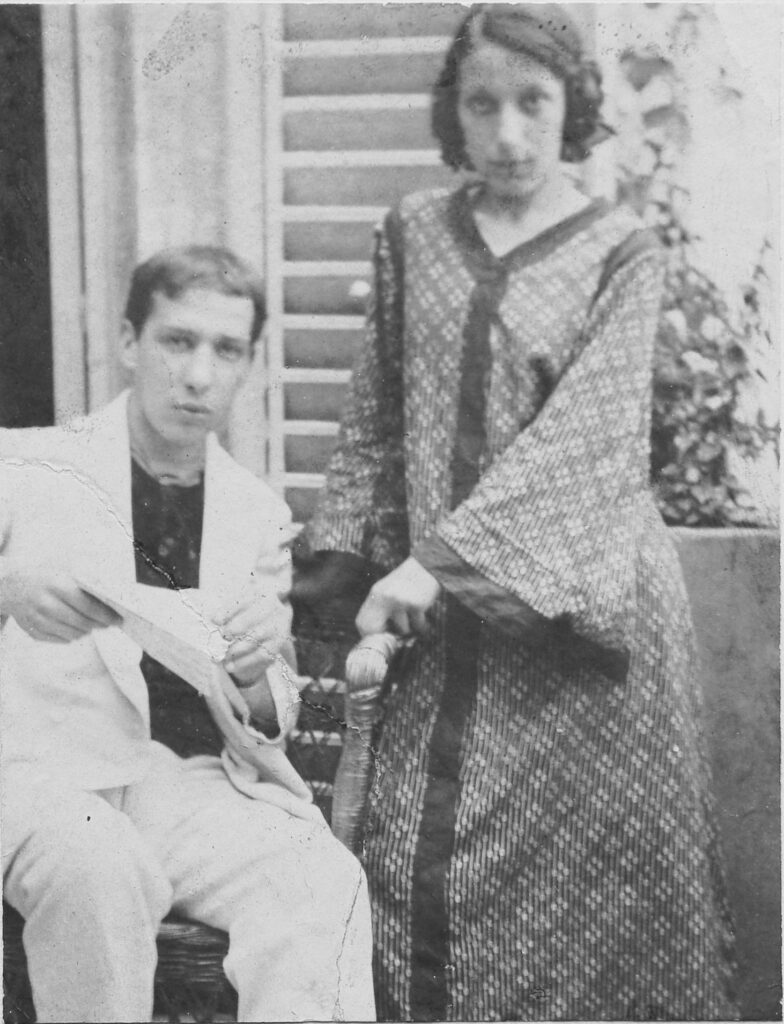

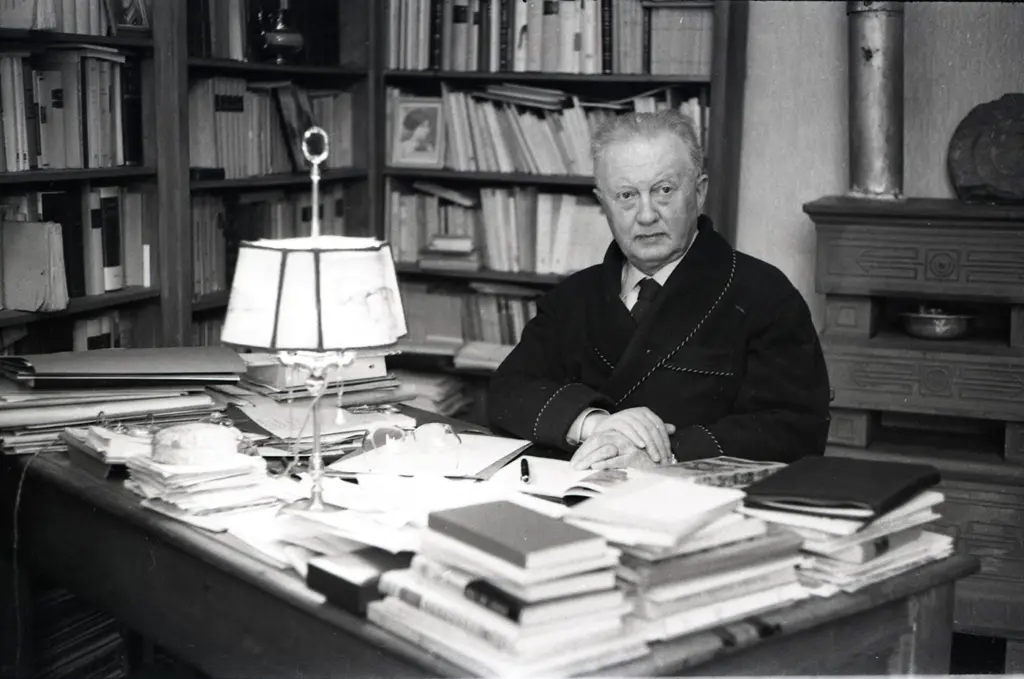

Umberto Saba, Virgilio Giotti, Carolina Wölfler, 1910 – coll. Centro Studi V. Giotti

From Grado to Dalmatia passing through Ponterosso, tuto un remitùr*

The language of writers who use dialect is both archaic an very modern: tradition and experimentalism together

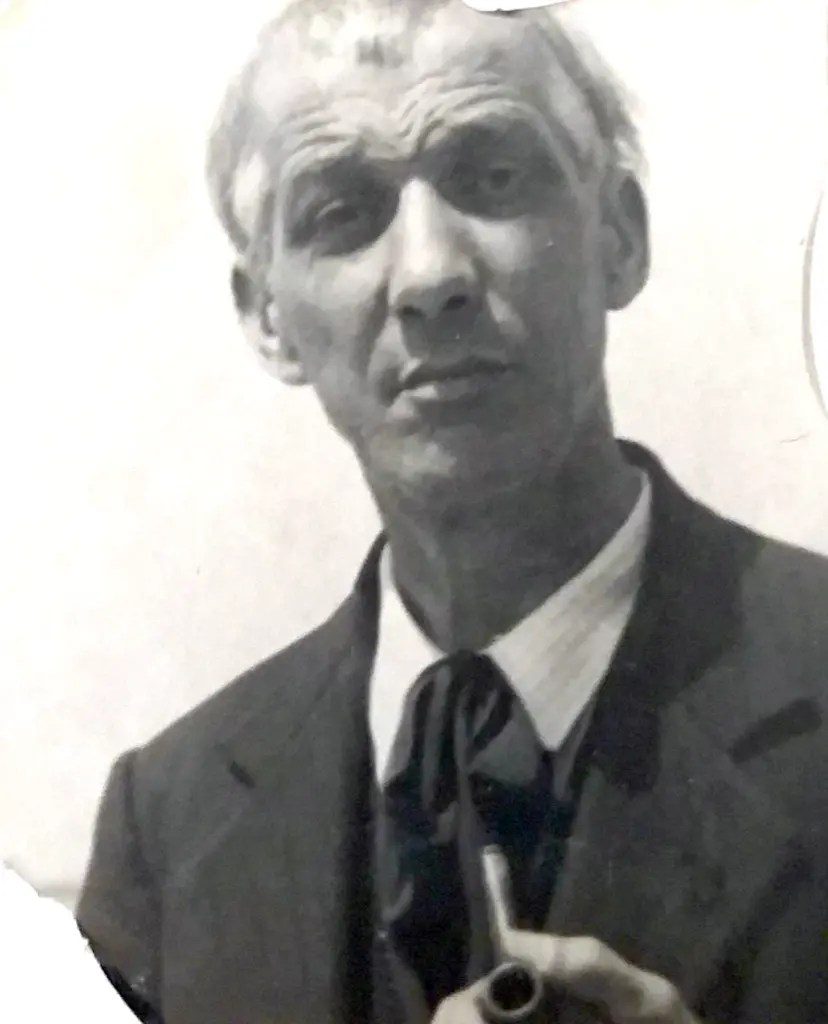

Biagio Marin

The musical dialect of the Grado lagoon – a seaside resort and dreamy tangle of islets and canals, fishing boats and thatched fishermen’s huts – is the backdrop to the unmistakable sound of his poetry. Having also trained in Florence, and then in Vienna and Rome, for a while he ended up managing the Grado tourist board. From 1941 to 1956 he found serenity and economic security in Trieste as head of the Assicurazioni Generali Library.

Lino Carpinteri and Mariano Faraguna

A partnership launched in 1945 and continued on in “La Cittadella“, a satirical weekly in the “Piccolo” until 2001, these tell of a popular and lively Trieste-Istrian-Dalmatian Central Europe in the Maldobrie (1966 -1983), an epic of the navigation of the inhabitants of the old provinces of the defunct Empire, and in the lyrics of Serbidiola (1964), a nonsense word derived from the incipit of the Hapsburg anthem in Italian: Serbi Dio l’austriaco regno…

Claudio Grisancich

As a twelve-year-old he was fascinated by the voice of a woman reading a poem in dialect on the radio. That woman was Anita Pittoni who soon welcomed him into her living room and, in 1966, published Noi vegnaremo, the first of a long series of poetic collections, almost all in dialect. Employed – like Marin – at Assicurazioni Generali, his life has been entirely in the name of Trieste’s literature, including a difficult but key relationship with Pittoni, a degree thesis on the writer Renzo Rosso, and on the the radio with Giorgio Pressburger.