The Commiato to Cose leggere e vaganti (“Envoi” to “Light and Airy Things”) of 1920, illustrated by the poet Virgilio Giotti, is a sort of visual synthesis of the genesis of the Canzoniere. Saba’s lyrics often wander between one another of the twelve editions approved by the poet until the canonical collection of 1945. Like bubbles, some poems float, changing in their reflection or colours. Others explode, leaving only a trace. We can observe them with the “optical instrument” prepared by Saba, the Storia e cronistoria del Canzoniere (“History and Chronicle of the Canzoniere”, 1948) in which the poet criticizes his own work while signing himself Giuseppe Carimandrei.

The publication of the Canzoniere in 1945 did not exhaust the poet’s vein in Saba and did not calm his anxiety to remake himself and the world through poems. After three years Einaudi printed a new Canzoniere (1948) in which many errors from the previous edition were corrected and the lyrics of the new “Mediterranean” anthology (1946) were inserted.

This was followed by some re-editions of the various collections (which gave substance to the old project of publishing the Canzoniere “in installments”), together with new works – including “Birds”, which came out under Anita Pittoni’s ‘Zibaldone’ publishing house – as well as other editions of the Canzoniere with small variations, followed, finally, by the “testamentary” collection, “Epigraphs”.

A mia moglie

Tu sei come una giovane,

una bianca pollastra

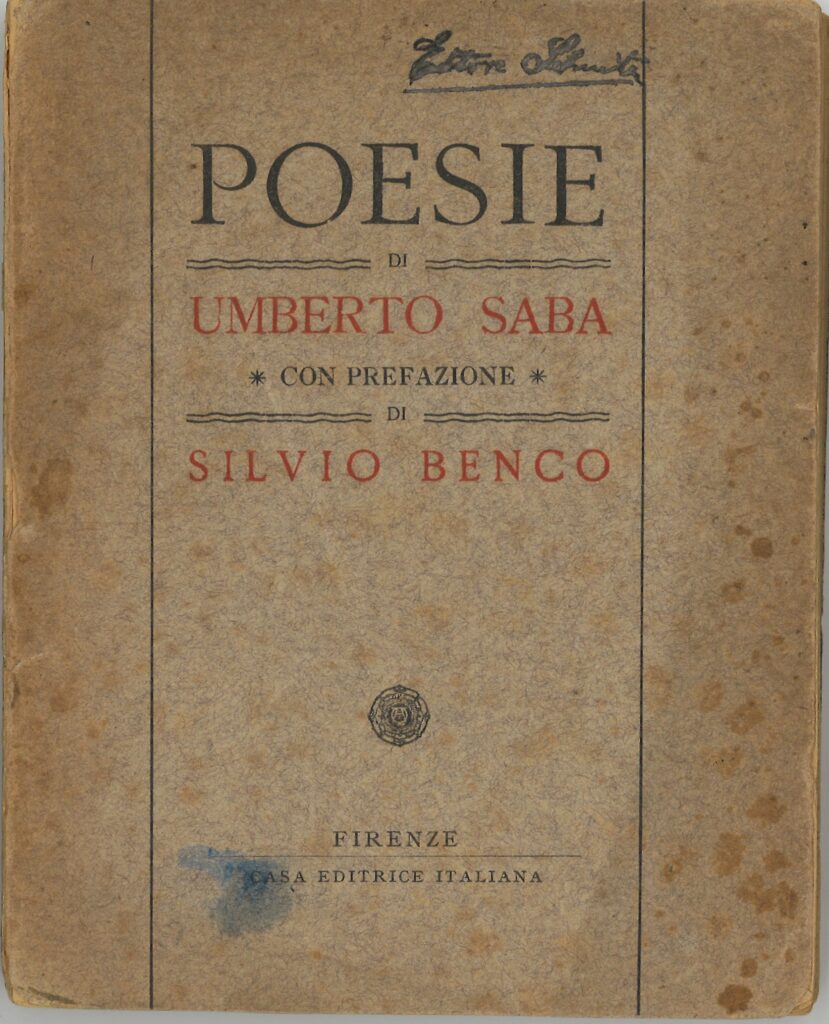

Umberto Saba, Poesie

Firenze, Casa editrice italiana, 1911

This is the book in which the poet signs himself “Saba” for the first time. This youthful poetic biography is “the first – very wrong – book of verses”. It ends with the lyric A mia moglie (“To My Wife”) in which he compares his young wife to ”all | the females of all | the peaceful animals | who are near to God”.

1912

Trieste

La città dove vivo à una selvaggia

grazia, che adulta serba il bello e il rozzo

d’un ragazzaccio con le mani troppo

grandi per dare un fiore:

è torbida come un amore

con gelosia

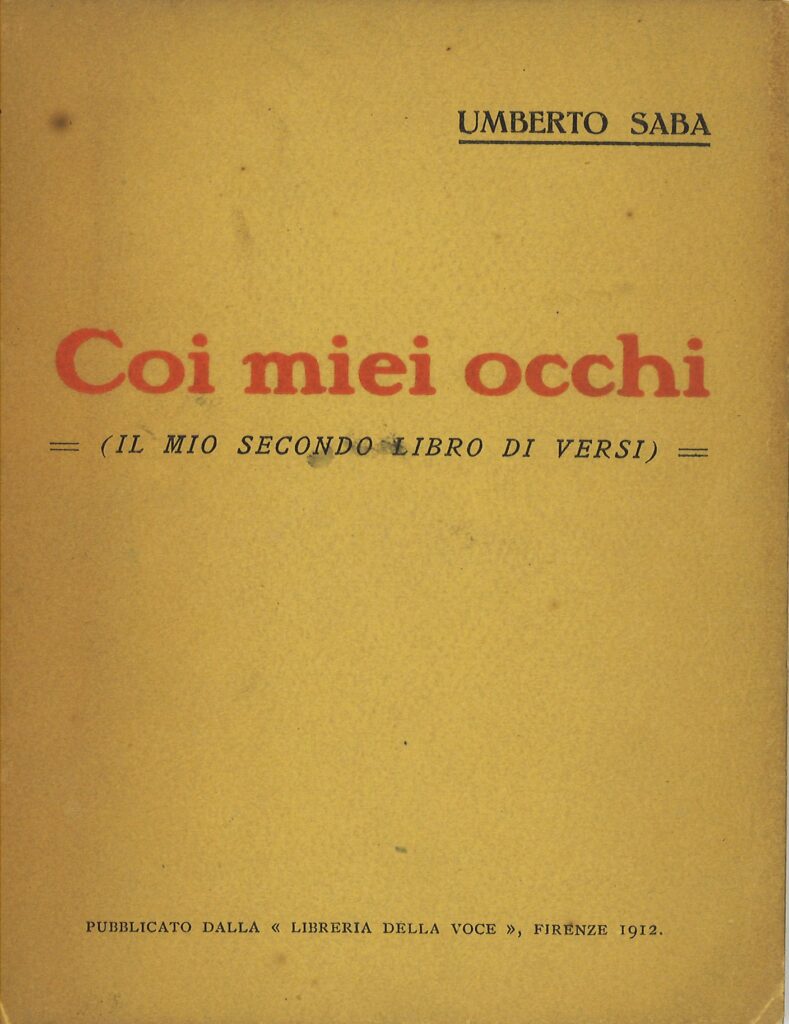

Umberto Saba, Coi miei occhi. (Il mio secondo libro di versi)

Firenze, Libreria della Voce, 1912

“A square booklet, with a yellow cover, and the title printed in red: the colours of Carmen […] a character described by Mérimée and sung by Bizet” which embodies Lina’s sensual exuberance. From 1919 the collection was to take the title Trieste e una donna (“Trieste and a Woman”) and remained thus. “In Trieste the poet finds a “surly” grace that pleases him. […] In the editions preceding the Canzoniere of 1945 he called it “wild”: he found the right adjective when writing, many years later, Distacco (“Separation”) in Parole (“Words”, 1934) and brought it back to the definitive draft of that poem, where the the adjective “surly” is better suited to the image of the boy”.

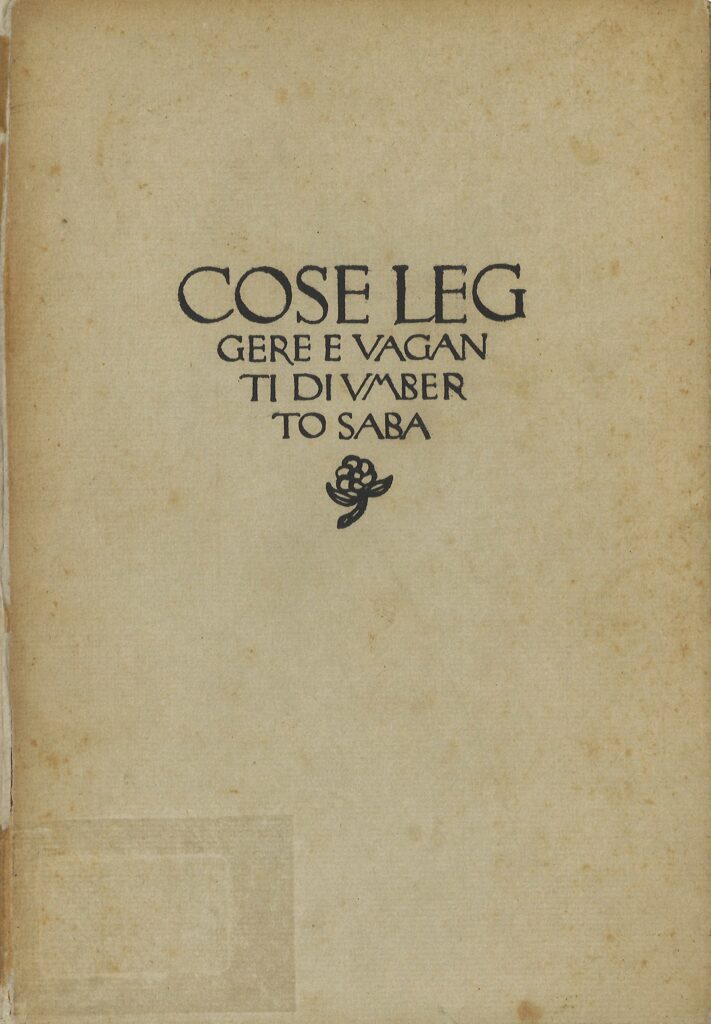

1920

I poeti

Scrivere su vecchie carte versi nuovi

è mio sommo piacere

Umberto Saba, Cose leggere e vaganti

Trieste, La libreria antica e moderna, 1920

Plaquette in 35 numbered copies. “The collection includes twelve short poems; the thread that binds them is […] the euphoric air of (illusory) freedom that one could breathe in the years that immediately followed the First World War […], the state of mind that inclined the poet to love the things that, due to their lightness, wander, like happy appearances, above and through the heaviness of life”.

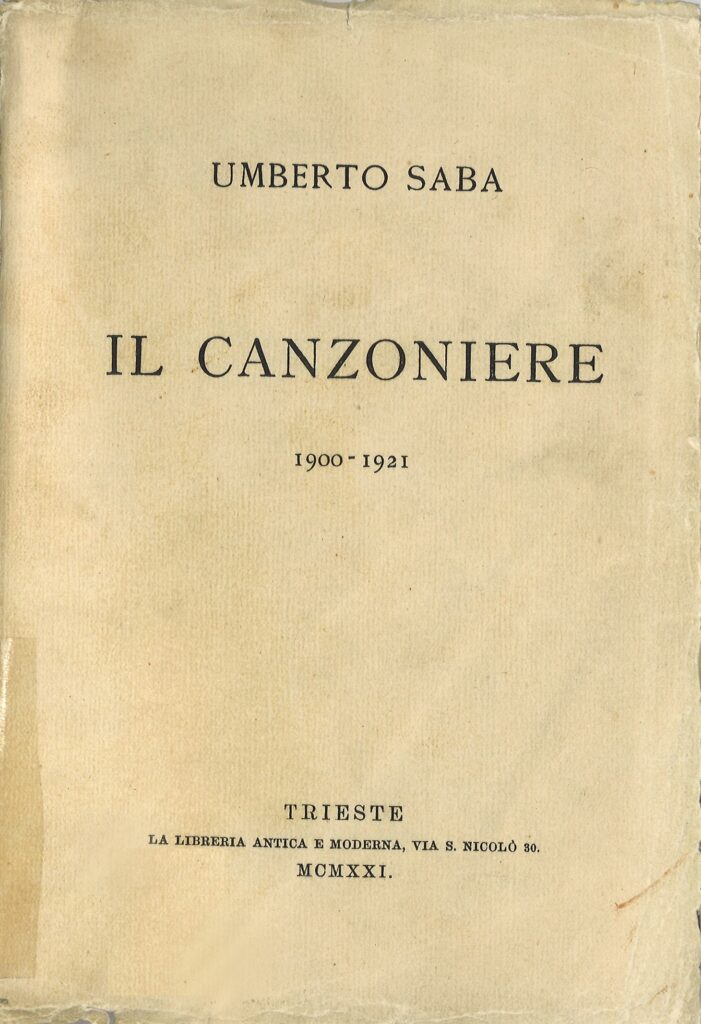

1921

Glauco

Umberto, ma perché senza un diletto

tu consumi la vita, e par nasconda

un dolore o un mistero ogni tuo detto?

Umberto Saba, Il Canzoniere 1900-1921

Trieste, La libreria antica e moderna, 1921

“It included less than a third of what was supposed to be the complete work. It was a book of 222 densely printed pages and limited to only 600 copies”. The first Canzoniere integrates, in a new lyrical structure, verses from the years 1912-1918 published in magazines with those of L’amorosa spina (“The Loving Thorn”, 1920) which closes the collection. The Poesie dell’adolescenza (“Poems of Adolescence”), discarded in the 1911 edition, were now rediscovered: “the only ones that I love, the only ones that I repeat to myself sometimes and which, in short, give me no reason to repent or mourn”.

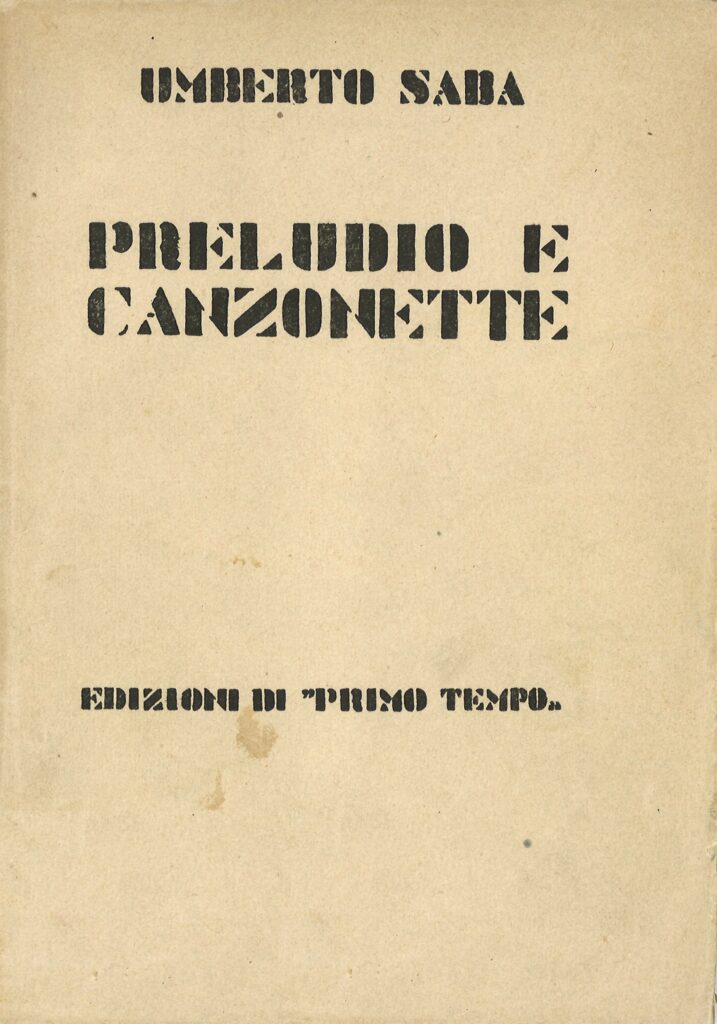

1923

Il canto di un mattino

E l’udivo cantare,

per se stesso, ma si che la città

n’era intenta, ed i colli e la marina,

e sopra tutte le cose il mio cuore

Umberto Saba, Preludio e canzonette

Torino, Edizioni di Primo Tempo, 1923

“At the time that Saba wrote his canzonette (little songs), one song was very popular on the streets of Trieste […]. It said: ‘This, my little one, this is no good’; saying that if love was to be a torment, it was better to say goodbye to it forever and never think about it again. No wonder Saba liked the ditty, that perhaps he owed to it the idea of writing the canzonette”.

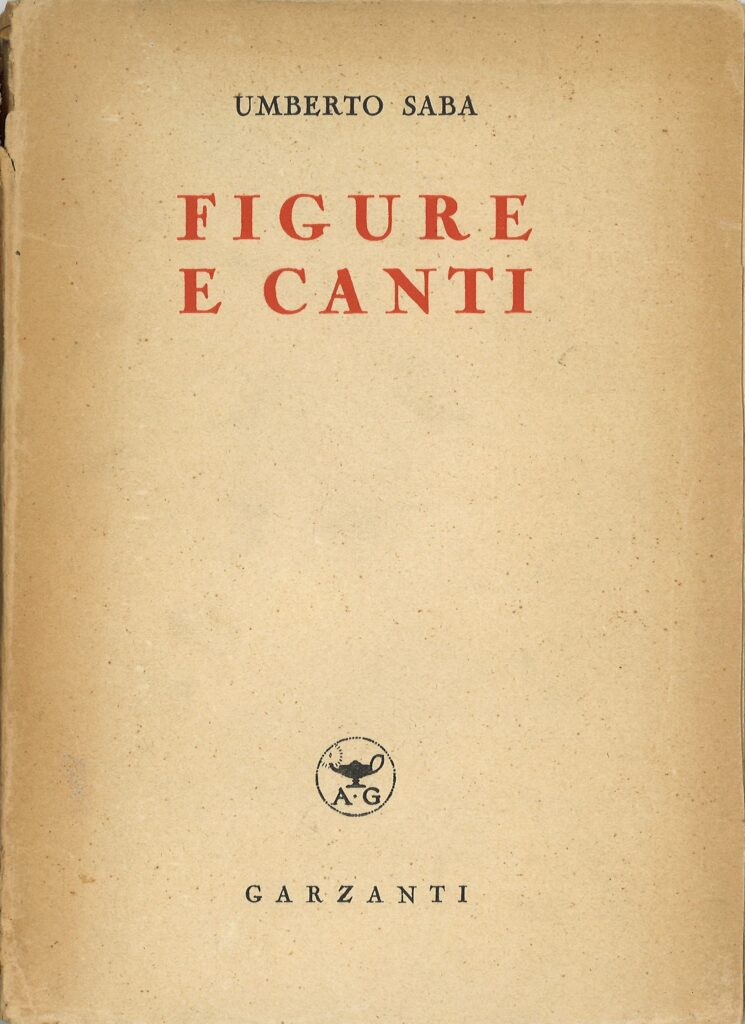

1926

Il Borgo

Fu come un vano | sospiro

il desiderio improvviso d’uscire

di me stesso, di vivere la vita

di tutti,| d’essere come tutti

gli uomini di tutti | i giorni.

Umberto Saba, Figure e canti

Milano, Fratelli Treves, 1926

The first collection released by an important publishing house contained the production following the Canzoniere of 1921. The title was a tribute to Giacomo Debenedetti who, in his first essay on Saba (1929), uses ‘figures’ and ‘songs’ to define the most characteristic elements of his poetry, that of epicism and autobiography. ll Borgo (“The Village”) “reflects a part of the human drama of Saba, and of all men like Saba, condemned by internal fatality to a kind of proud, involuntary solitude”.

1926

L'uomo

Era, con tutta la sua forza, in mano

del Fato

Umberto Saba, L’uomo

Trieste, giugno 1926

A short poem distributed to friends, printed in 25 copies. “With it, Saba set out to write – summarized in one figure – the natural history of all men […] everything that generally happens to the human animal: being born, procreating, aging and dying’’. L’Uomo, (“The Man”) not La capra, (“The Goat”) is a Jewish poem. And Saba’s “Man” is certainly an Old Testament figure”.

1928

Preludio

Oh, ritornate a me voci d’un tempo,

care voci discordi!

Umberto Saba, Preludio e fughe

Firenze, Edizioni di Solaria, 1928

Le Fughe sono «voci che si parlano fra di loro, s’inseguono per dirsi cose ora contrastanti, ora concordanti. […] sono in realtà la voce di Saba; l’espressione – diventata poesia – del sì e del no che egli disse alla ‘calda vita’, amata ed odiata al tempo stesso». L’occasione che dà il la alle Fughe è la strana idea di «suonare il violino sul piano, come gli diceva più tardi, ridendo, Italo Svevo»: di suonare Bach, ma a parole.

1929

Tre poesie alla mia balia | Insonnia

Eccola: è viva; in piedi dopo tante

vicende e tante stagioni. Un sorriso

illumina, a vedermi, il volto ancora

bello per me, misterioso.

Umberto Saba, Tre poesie alla mia balia

Trieste, Tipografia Vittorio Levi, 1929

“Thirty copies, out of print, for the Author’s Friends” represent the entire edition of this collection of three poems composed in August 1929. They are the first fruits of the psychoanalytical treatment undertaken during that summer with Edoardo Weiss, the initial nucleus of the collection Il piccolo Berto (“Little Berto”) in which the poet goes in search of the figure of his old nurse, who emerged during the sessions.

1932

Ammonizione

Che fai nel ciel sereno

bel nuvolo rosato,

acceso e vagheggiato

dall’aurora del dí?

Umberto Saba, Ammonizione ed altre poesie. 1900-1910

Trieste, 1932

“Printed on behalf of the author and edited by Virgilio Giotti” takes up a 1920 project for a Canzoniere divided into several volumes. Once again the “Poems of Adolescence and Youth” are rearranged, examined and selected.

1933

Berto

“Berto – gli dissi – non avere paura.

Io ti parlo così, sai, ma non oso,

o appena, interrogarti. Non sei tu,

tornato all’improvviso, il mio tesoro

nascosto? Ed io non porto oggi il tuo nome?”

Umberto Saba, Tre composizioni precedute da un’Appendice e da Figure e Canti

Milano, Roma, Treves-Treccani-Tumminelli, 1933

This book contains the verses that make up the collection Il piccolo Berto (“Little Berto”). “It is a kind of ‘amorous conversation’ between the poet who was close to fifty and the child who had been (or imagined having been ) […]. “Little Berto” never completely died, and, had this happened, Saba would have completely recovered and would no longer have written poems, “because he would no longer have needed to write them”.

1934

Il lago

Piccolo lago in mezzo ai monti – il giorno

le calde mucche bevono ai tuoi orli;

a notte specchi le stelle – mi sento

oggi in un brivido la tua chiarezza.

Umberto Saba, Parole

Lanciano, Carabba, 1934

1945

Avevo

Avevo una città bella tra i monti

rocciosi e il mare luminoso.

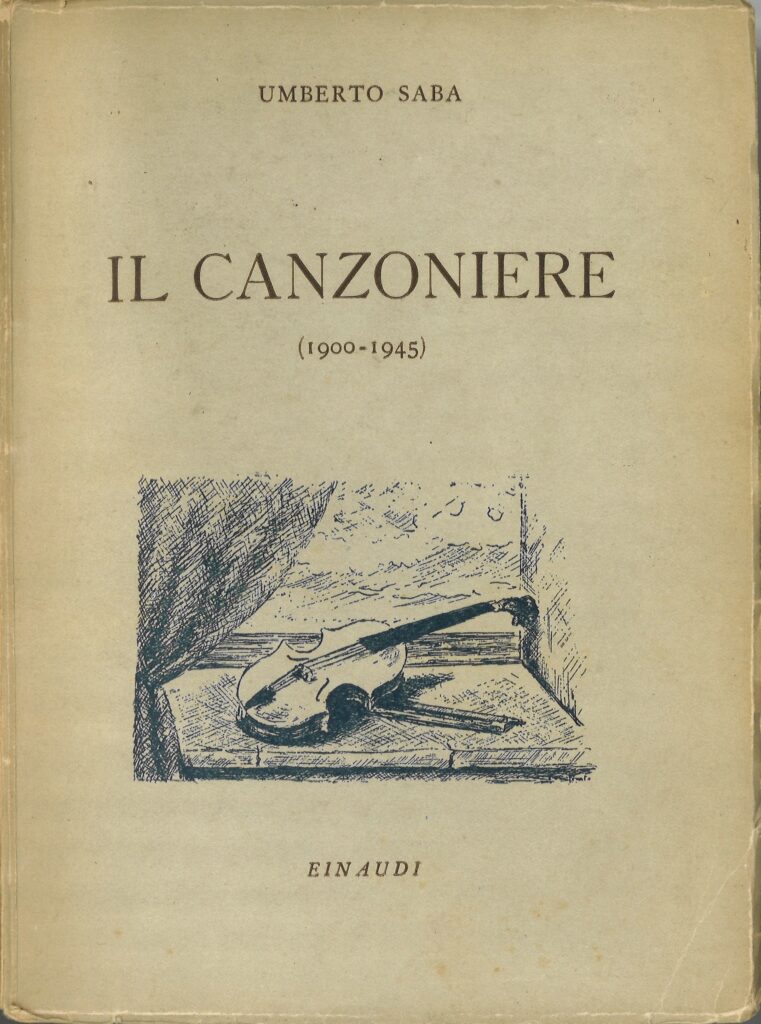

Umberto Saba, Il Canzoniere (1900-1945)

Roma, Einaudi, 1945

“The Canzoniere is the story, the ‘psychological novel’ of a life”. It was published by Einaudi 24 years after the first collection. Saba worked on it incessantly during the World War Two, without being able to resort to either his already printed books or his friends, and relying only on his own memory. “The task of poetry” is to “bring us back ‘to the dark womb of the world’”.