1719: The Big Bang

The drawing – board city

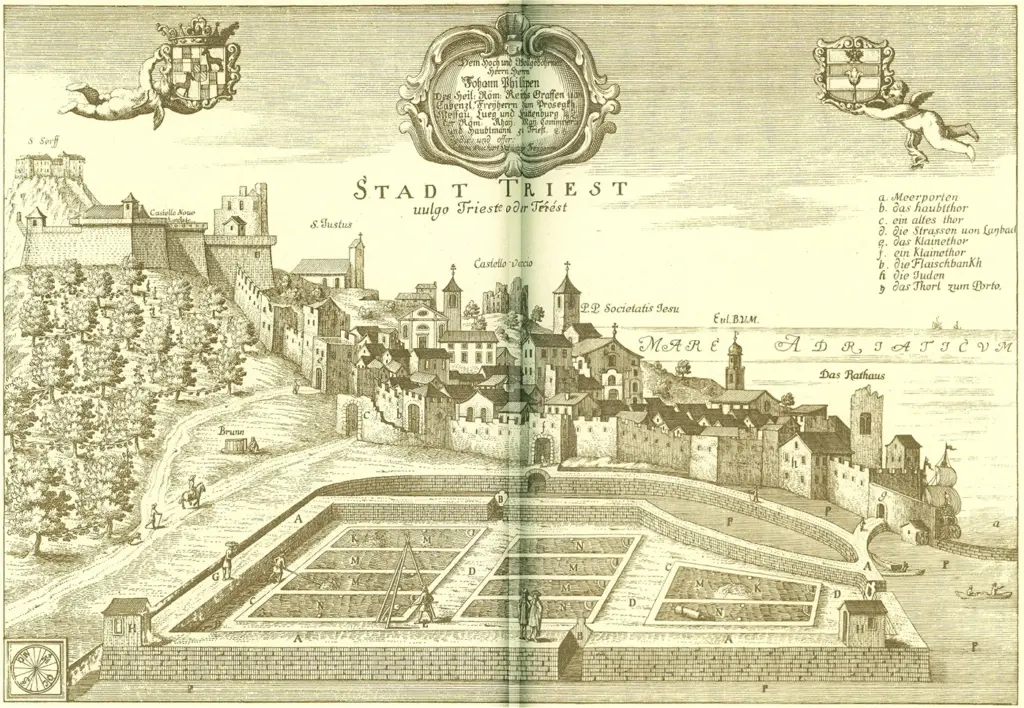

In 1718, the city was still within the medieval walls. The scrupulous indication of the depths of the seabed served to suggest that the coastline was suitable for the new port of call. The port, an emporium of the Habsburg Empire, is an artificial city, desired by Vienna “drawn up on a geographical map and governed by written rules” (Tomizza). It was the laws dictated by Empress Maria Theresa that encouraged immigration, established freedom of worship and opened consulates, expanded port facilities, and redesigned the urban layout: in 1780 the old city was united with the Borgo Teresiano.

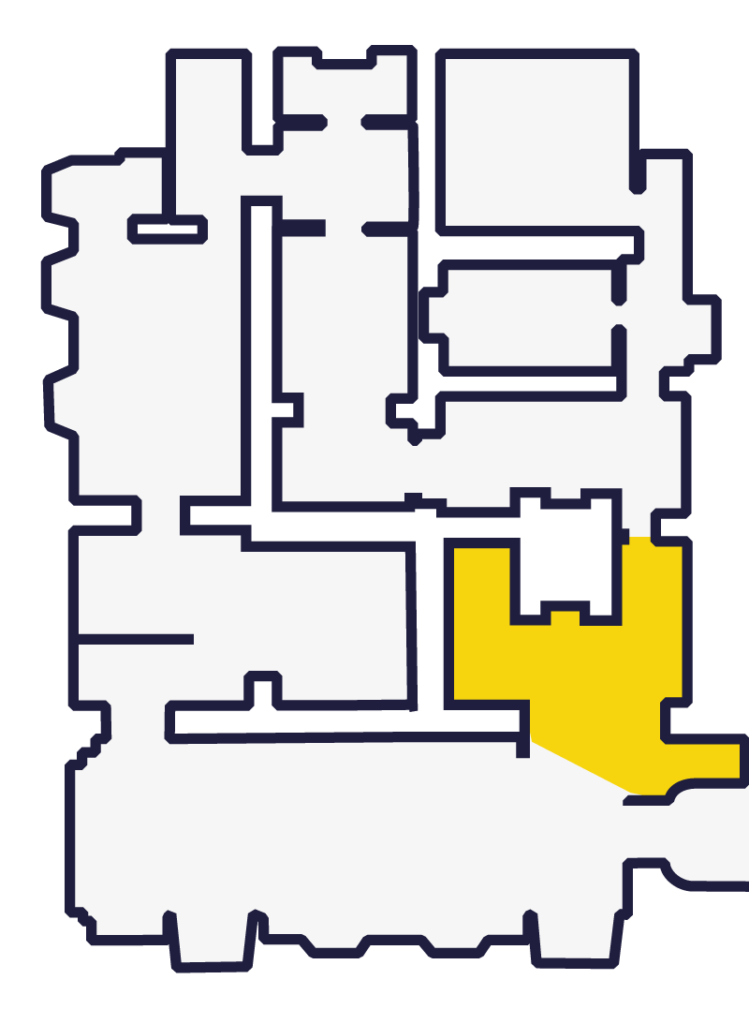

Pietro Kandler, Cartolare di Piani e Carte dal quale fu tratto l’albo presentato allo Imperatore nell’autunno, 1856 > coll. BC Hortis | 1. tav. 291 Planimetria di Trieste

Trieste del “sì”, del “ja”, del “da”*

* Carolus Cergoly, Latitudine nord, 1980

The multi-faith city

Postcard

In addition to trade, various communities were attracted to Trieste by the religious tolerance granted by (...) OPEN

Population of Trieste*

Before the war

In the period leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, European geopolitical events were intertwined with the city’s continuous demographic and economic expansion and the demands for renewal coming from ever larger sectors of the population.

In 1863 the Triestina Gymnastics Association was founded, and in the following years it was dissolved five times by the Austrian authorities for the irredentist positions of its members. In 1903 the Workers’ Cooperatives of Trieste, Istria and Friuli were formed, with the aim of improving the living conditions of workers through mutual aid initiatives and the establishment of savings funds.

Inhabitants of the San Giacomo district in front of the Cooperative Workers’ shop, 1903 > courtesy Lucio Fabi

The war at home

In July 1914 the coffins of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary and his wife Sophie, killed in an attack in Sarajevo, arrived in Trieste. It marked the beginning of the First World War. 50,000 Triestines, mostly Italian-speaking, were sent to Galicia, on the Russian front, but when Rome entered the war against Vienna, many irredentists crossed the border to join the Italian army.

At the end of the war, on 3rd November 1918, the destroyer Audace docked at the “San Carlo” Pier, since then called the “Molo Audace”, and the city, the only port of the Austrian Empire, became part of the Italian state.

The riots of 1915

When Italy declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire in May 1915, a part of Trieste’s population rose up, attacking the symbols of Italian culture in the city. Italo Svevo testified to those moments in his diary: The “Piccolo” is on fire. In the clear, moonlight evening the gigantic red flames are licking the houses on the side of the Barriera Vecchia district and now the roof of the Monte di Pietà which lies on the other side. […] The looters and arsonists are in very good spirits.

Nobody is stopping them. A breathless woman with grubby hands and a damp forehead approached us, emerging from the nucleus of people carrying out the destruction. I think something was stirring in her conscience because she approached me, feeling the need to have my approval:

– “We are all Italians. But they’ve been too dirty about it, making war after we have suffered so much for these ten months.”

Piazza Goldoni, formerly Piazza della Legna, headquarter of the newspaper, 1900 ca. > coll. BC Hortis

Between one and the other war

Once the imperial administrative structures were dismantled and the Austrian employees emigrated, the city officially became Italian with the Treaty of Rapallo of 12 November 1920 and the new state committed itself to the effort of replacing the declining port activities with industrial development policies. At the same time, the city experienced the advent of Fascism, which inaugurated a policy of denationalisation and violence against the Slovenian-speaking population.

In a complex context characterised by political clashes, national issues and cultural and linguistic factors, there is the serious episode of the fire at the Hotel Balkan, the seat of the main Slovene cultural institutions. In 1938, from a stage near the Town Hall in Piazza Unità d’Italia (formerly Piazza Grande), Benito Mussolini announced the racial laws intended to discriminate against the Jewish population.

The Second World War

In 1940, Italy entered the war alongside Germany and occupied a large part of Yugoslavia. At the fall of Mussolini in 1943, the Germans created the Adriatic Coastal Operation Zone – Adriatisches Kűstenland – effectively placing the city of Trieste under the authority of the third Reich and experienced the horror of the ‘Risiera’ of San Sabba in which Giani Stuparich was also imprisoned. In 1944 heavy bomber raids by Allied forces destroyed a large part of the industrial aream, and with it Italo Svevo’s villa. In May 1945, as the war drew to a close, Tito’s Yugoslav troops entered the city and occupied it for forty days, carrying out a harsh repression against political opponents and all those who opposed the annexation of the city to Yugoslavia. The Anglo-American allies take over in June and establish the Allied Military Government (AMG), which is followed by the establishmen of the Free Territory of Trieste (FTT) in 1947

The San Sabba Risiera

In Trieste the word “risiera” has an anguished meaning. In the autumn of 1943 the Nazi command led by Odilo Globočnik, a Trieste native German speaking of Slovenian origin, took possession of a rice processing factory in the outlying district of San Sabba, making it a place of detention, for the sorting of prisoners, political opponents and Jews, destined for the camps of northern Europe, for violence and murders.

Historians believe 20,000 prisoners passed through the camp and that at least 5,000 victims were incinerated there. The building was transformed into a museum and declared a National Monument in 1965. 699

Risiera di San Sabba, outside view, 1975 ca. > coll. Fototeca CMSA – ph. Alfonso Mottola

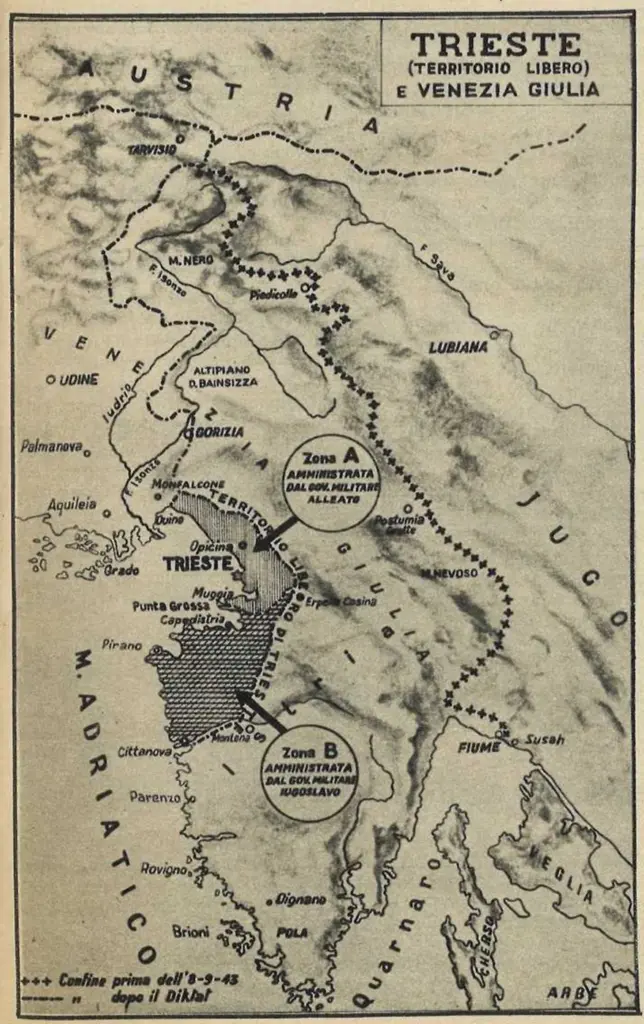

FTT Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste (in English: Free Territory of Trieste; in Slovene: Svobodno Tržaško Ozemlje) is an independent state provided for in Article 21 of the Treaty of Paris signed between Italy and the Allied Powers in 1947 that was never legally constituted. Planned as a demilitarised and neutral territory, it was ruled under a provisional regime by Anglo-American troops, who were supposed to rule it until the appointment of a governor, which, however, never happened. A condition of suspension, far from being ‘pacified’, on which the phenomenon of the exodus of the Italian population from the territories of Istria was intertwined and on which the November 1953 uprisings had an impact, during which six demonstrators fighting for the Italianness of Trieste were killed. On 5 October 1954, in London, a memorandum of understanding was signed between Italy and Yugoslavia: Trieste remained under the control of the Italian civil administration (Zone A), part of the Istrian peninsula (Zone B) went to Yugoslavia.

City of science

Postcard

A ‘system of excellence’ has repeatedly been defined as the one that has led to Trieste (...) OPEN

War and Peace: Diego de Herniquez

A scholar and collector of war memorabilia, author of informative diaries, de Henriquez began to develop a passion for relics of the First War as a child, during walks in the Karst. During the Second World War he collected the spoils of war by dealing with the various commands that alternated in the occupation of Trieste. An eccentric character, who slept in a coffin-shaped bed, he died in a fire in the warehouse in which he lived in 1974. There were many doubts about the nature of the incident, which some trace back to uncomfortable secrets contained in his diaries, and which enlivened the judicial and journalistic investigations. His story and his precious collection gave life to the “War for Peace Museum” that carries his name and to Claudio Magris’s novels, Non luogo a procedere (translated as Blameless) and Veit Heinichen’s Der Tod wirft lange Schatten (which means “The Long Shadows of Death”).

Diego de Henriquez in his outdoor war relics store in Trebiciano, 1971 > coll. CMDH

A long postwar

It was only with the 1975 Treaty of Osimo that the provisional administration areas of the FTT were definitively assigned to the two neighbouring states: Trieste was Italian, Istria Yugoslavian. With the new arrangement following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the violent dissolution of the Yugoslav federation, the Julian port seemed to regain its geopolitical and economic role and Trieste its centrality.

In 2004 the Schengen treaty extended to Slovenia, and in 2022 to Croatia, breaks down – even physically – the borders on which Trieste has woven its history. The border becomes ‘invisible’, free movement fosters exchanges and relations between states in a Europe that is faced with ever new challenges.”

The exodus

The exodus of the Italian-speaking populations from Istria, Dalmatia and Kvarner archipelago has proved a traumatic and painful event for several generations who abandoned everything and crowded the refugee camps set up in the province of Trieste, often choosing the path of emigration towards Australia and the Americas.

However, many remained in Trieste, which once again saw the composition of its population changing. The Istrian Fulvio Tomizza was one of the writers who recounted this collective drama.

The exodus of the Istrians, 1955 > courtesy I.R.C.I. Istituto Regionale per la Cultura Istriano Fiumano Dalmata

-Nita, are you happy if we go to Trieste?

-When?

-Soon

-And when are we coming back?

-No, we’re not coming back. We will stay in Trieste forever

-Us as well?

-Us as well.

-And the bubune (oxen)?

-And we will take the bubune with us.

-And is there somewhere to graze them in Trieste?

-We will find somewhere.

-And will uncle go to graze them?

-We will see. Why, wouldn’t you want to go too?

-I do. By now they know me, they even let me guide them to graze. But there are lots of cars in Trieste. How will I manage to graze them with so many cars?

-We will take them where there are no cars. And then there’ll be Fido to keep them under control, won’t there?

-But won’t there be a danger of him biting someone? Is it true that there are many foreigners in Trieste?

-That’s true. But go to sleep now.

From Materada, di Fulvio Tomizza, 1960

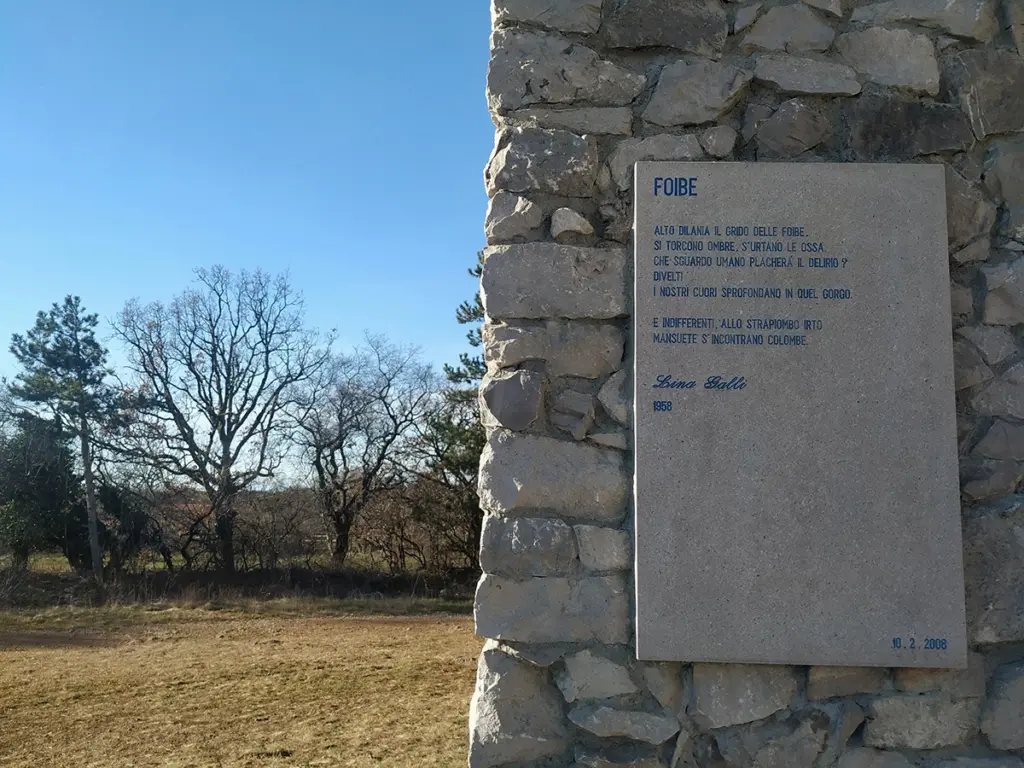

Foibe

The word “foiba”, derived from the Latin fovea (pit), is also a word loaded with painful meanings in Trieste. In the deep karst cavities scattered on the plateau and in Istria, the victims of the violence perpetrated by Yugoslav partisan formations against soldiers and civilians, mainly Italians, and those who opposed the new socialist state led by Marshal Tito, were plunged.

Of this violence, the Foiba of Basovizza, a disused mine shaft on the Trieste Karst, declared a national monument in 1992, is the symbol.